THE RACE

A trail race is not a road race. Two marathons do not a 50-mile race make. Two 50-mile races don’t make a 100-mile race. And a “typical” 100-mile trail race is not a Western States Endurance Run.

For runners, climbing 18,000 feet and descending 23,000 feet across 100 miles of treacherous mountain trails during the heat of the day and chill of the night requires a totally different level of physical, mental, and logistical preparation. For the race director, orchestrating 1,500 volunteers across 25 aid stations in the Sierra Nevada to serve 400 runners during more than 30 hours is simply mind-boggling. But somehow, for 30 years now, it all comes together for the runners and the race director on the last weekend of every June.

Originally used by the Paiute and Washoe Indians, the Western States trail served for many years as the most direct route from the silver mines of Nevada to the gold camps of California. In 1955 a horse race was organized to prove that the 100-mile path from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California could be completed in 24 hours. This race, known as the Tevis Cup, became an annual event. In 1974, Gordy Ainsworth was the first man to join the horses on foot and completed the race even ahead of some of the horses. By 1977 the foot race had become an organized event and a year later was held separately from the horse race. Today, both races are held about three weeks apart, attracting contestants from across the world. Some 3,500 endurance athletes have finished the foot race and some have even finished both!

My race started about 18-months back when I qualified to Western States by running the, now in hindsight very easy, JFK 50-mile race in 8 ½ hours. Because there are more applicants than spots to the Western States race, an annual lottery is conducted to grant entries to the race. Being a non-profit organization that is always looking for funds to maintain and protect the trail, it also sells tickets to a raffle for two of the spots every year. With the purchase of enough raffle tickets, I knew I would have a better than a fifty-fifty chance at a winning entry, which is in fact exactly what happened.

With a race entry in hand and eighteen months to the race, all I needed to do was train. But how in the world do you train to run 100 miles across mountains, particularly for someone with very average running talent? For me, there was only one answer: learn from the best. So I hired seven-time Western States champion and course record holder, Scott Jurek, as my coach. Too bad he couldn’t also do the running for me.

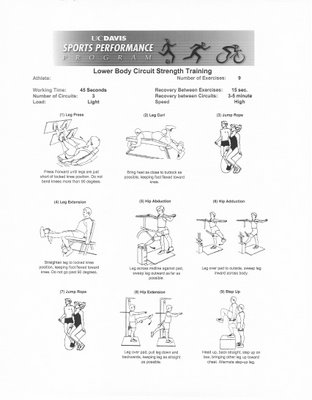

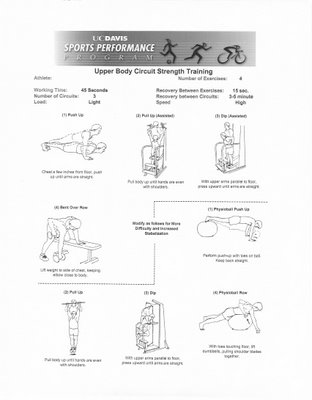

Training for any race is a process of building a base, then sharpening and finally peaking on race day. Building a base requires months of long, slow distance running. Sharpening increases the intensity of the runs, including interval training and runs at lactate threshold. If done correctly, a runner should be able to peak on race day. These phases are completed through a process of stress and recovery during which the intensity of the workouts increase every week for three weeks followed by a one-week recovery at about half the intensity of the prior week. The four-week training cycle is repeated over and over (and over and over), at ever increasing intensities. Add to that a twice a week weight, strength-training program, an occasional 50-mile training race, hydration and nutrition testing while running, and you’ve got yourself the equivalent of a full-time job. Culminating a month before the race with about 20 hours of running per week, I often wondered which was more difficult and required higher discipline, the training or the race itself.

There is also a fine balance between injury and training. At such high mileage, the average body is prone to many injuries. I had my share of them, including a severely dislocated ankle (as in the bone out of the socket) just three months before the race. There is a saying at Western States that it is better to arrive to the race a little under-trained than a little injured, unfortunately most of us arrive there under-trained with injuries which the terrain has a phenomenal ability to uncover and exploit to increase its arduousness.

Eighteen months of training is a lifetime -- a lifetime during which I lost two of my closest friends to cancer, my father and my sister. The race took on a new meaning. It became my way to close these chapters of my life. It would also serve to rediscover my mental fortitude and to create a passage to a new phase of my professional career.

I spent the month prior to the race sleeping at 6,200 feet of altitude in Squaw Valley and training in the canyons during the heat of the day. It became apparent very quickly that the lack of mountains in Connecticut (where I live) was going to present a challenge during race day. I had tried to find the most difficult terrain in Connecticut, but the toughest mountains there are but gentle hills at Western States. During this last month, I met a good training buddy with whom I repeatedly trained on the last 70 miles of the course, including the last 20 at night. Coincidentally, we both had identical VO2 max levels and could run 1000-meter intervals at exactly the same speed, but his mountain training had made him a much stronger endurance runner. He would seemingly effortlessly run up the mountains, as I was left gasping for air far behind. He would run graciously down the steep slopes as if his steps had been choreographed to dance between the stones, while heavy-footedly, I would clumsily hold on for dear life.

My family and crew joined me at Squaw Valley a few days before the race. We spent a day visiting five of the twenty-five aid stations where they would crew for me. Because of the distance between the aid stations and times of the day during which I would pass by them, we spread aid-station responsibility among the crew. My pacer would take the aid station at mile 30 and then pace me from mile 60 to the finish line. Everyone would see me at miles 55, 62 and 100. And my nephew and his friend would handle night duty at miles 80 and 93.

Even though I had planned on retiring to bed early the night before the race, all the preparations with my crew prevented me from getting to bed before 11 pm. It was difficult to know exactly what I would need when, so my crew had to be ready for all eventualities. Change of shoes, change of socks, extra salt tablets, food which I might or might not want, blister repair kits, hot weather gear, cold weather gear, ice for my cap and bandana, toilet paper kits (baby wipes and paper towels), extra bottles, insect repellent, tylenol, tums, gas tablets, etc. Each member of my crew of five had a specific responsibility and each had to know what was expected of them. Everyone had to know what was in the crew bag, where it was, and when was I likely to ask for it. “Keep the large ice cooler in the car with all the food and carry small coolers to the aid stations. Give me the flashlights and headlight at mile 62, unless I arrive after 8:00 pm at mile 55, in which case I need them then.” Even with five pages of written instructions, the logistics can be unnerving for the crew, which must be attentively waiting at the aid stations for hours, ready to crew for a minute or two at most.

I laid out all my gear at a table before retiring to bed. Though I was staying right at Olympic Village, within a 5-minute walk of the 5:00 am start, I still made plans to wake up at 3:00 am, as I needed sufficient time to have some breakfast and tape certain portions of my feet to prevent blisters. In bed by 11:00, I was still tossing and turning by 1:00 am as my mind was being haunted by self-doubt. I had volunteered at a 100k race in Connecticut three months back. The director for that race, an accomplished ultra-marathoner who had even finished Badwater, the infamous 135-mile ultra across Death Valley, had failed to advance past mile 30 at Western States the prior year. The other volunteer at my aid station there had attempted Western States five times, and never gotten past Devil’s Thumb (mile 49), yet he had completed more than twenty-five, 100-mile races. The winner of that 100k race, an athlete from Monroe, Connecticut was also running Western States this year; I, on the other hand, had never run past 50 miles (80k). An ultragirl friend of mine running Western States this year for the first time was already a veteran of ten Leadville 100-mile races. My much stronger training buddy had run the 50-mile Leona Divide a full one hour faster than me. All these self-doubting thoughts had me tossing and turning until I finally managed to clear my mind by 2:00 am, barely catching an hour of sleep before all three alarms went off at 3:00 am.

I was at the starting line by 4:20 am. All I needed to do was to get my bib number. The mandatory medical check-ups and the weigh-in had been completed the day before. The large chronometer at the starting line counts backwards. With ten minutes to go, all 400 runners assemble outside. The sun has yet to rise and at 6200 feet of elevation, it’s cold. Five minutes to go. The crewmembers, fans, and news media jostle for position at either side past the starting line to cheer the runners. With ten seconds to go, everyone starts counting backwards… and at the gun, we all hit our chronometers and go.

The adrenaline is high and it takes the runners 2,000 feet uphill over three miles to the first aid station unnoticeably fast. Each aid station has a sign at its entrance with the times for the 24 and 30-hour paces and the absolute cut-off at the next aid station. The lead runners run well ahead of the 24-hour pace. Experienced runners and many veterans of this race (3,500 runners have crossed the finish line 6,000 times) try to keep just under the 24-hour pace. Less experienced runners and novices of this race, like myself, try to keep their pace somewhere in between. Those struggling for a multitude of reasons, simply try to make the cut-off’s from aid station to aid station. Arrivals past the cut-off time to any aid station are automatically disqualified and must stop. Many, of course, arrive to the aid stations well before the cut-off but drop anyway from exhaustion, injury, or even total incoherence.

I reached the first aid station within a minute of the 24-hour pace. I don’t know how I got to there so quickly. I wanted to be around a 27 hour pace, right in the middle of 24 and 30 hours. “Heck, maybe this is easier than I thought,” I naively said to myself and continued on after refilling my water bottles and eating the rest of my crushed muffin.

The final push to the summit of Squaw Valley – Emmigrant Pass – starts a few hundred yards after the first aid station. This climb, while short, reduced me to all four. The only way for me to “scale” it without sliding down was using my hands and feet. My gloves helped me grab on to rocks and make my way up fairly fast and quite safe. At 8,700 feet, we reach the highest point in the race. The view from the top is inspiring – I can see the entirety of the mountains framed by Lake Tahoe at the valley and pink clouds from the first rising sun above. The air is crisp and draws me to contemplate the scenery, but this is not the time.

Theoretically, it’s all downhill from here as the finish line is at 1,280 feet of elevation. It’s just the additional 16,000 feet of vertical climb and 23,000 feet of descent that would create the challenge.

The next section of the course is supposed to be mostly down, that is, mathematically speaking. But I guess 51% down and 49% up would qualify for this definition. While beautiful with wild flowers and phenomenal vistas, the terrain is relentless with rocks and small streams that make footing difficult. Second aid station is at mile 12. I reached there right at the 30-hour mark. What happened? I didn’t think I had slowed down that much and only a handful of people, including Gordy, the race’s founder, had passed me. I’m doing fine though. I’m peeing frequently, an important barometer, which tells me I am well hydrated. I’ve been eating well and nothing hurts too much. My feet, despite getting a little wet from many of the streams, don’t show signs of blisters. “Just run the race within your limits and don’t worry about the time at this early stage,” I tell myself repeating the advice from many Western States veterans. I push it just a little bit faster to the next aid station.

I reach the Red Star Ridge aid station at mile 16 under 4 hours, but barely 3 minutes before the 30-hour pace. I’m in 268th place out of 400 or so. This means that there are about 130 runners behind me, but I also know that in all likelihood about 150 will not finish… which puts me too close to the tail. How can this be? I am running strong. Yikes, this is beginning to look like a 30-hour finish, and I don’t like it.

Enter Duncan Canyon section. An area devastated by a forest fire four years ago, it’s a desolate place with burnt trees, no foliage, and an imposing arid terrain which exposes the runners to the direct heat of the sun. I continue to hydrate myself, take salt tablets, eat, and run at a sustainable pace. I’m still in unfamiliar territory, as I’ve never covered the first 30 miles of the course (My training buddy and I had tried running this section before the race, but we got lost as this part of the course is not marked until a few days prior to the race.) I’m expecting some down hills since theoretically there is a canyon here somewhere, but the down hills never come or I miss them between the hills. I arrive to the aid station at mile 24 after 5 hours and 39 minutes. The 30-hour pace is 5 hours and 40 minutes and the absolute cut-off at this station is barely 50 minutes later. I don’t like my situation. I haven’t peed for an hour but perhaps I’ve been sweating more due to the heat of this section. I refill my water bottles, fill my pockets with some boiled potatoes, put ice in my cap and push on.

Six miles to the next aid station and the first medical check point where I will also see a member of my crew. I had told him that I would be there between 11 am and 1 pm; unbeknownst to me, he is rushing to get there on time, as the traffic is heavy and the parking situation difficult. I reach a river crossing, which I presume is the bottom of the canyon even though it feels as if I had ran up to the river. Many runners are cooling off at the river. I carefully step on rocks while holding on to a fallen tree so I don’t get my feet wet. Wet feet are the ideal breading ground for blisters. After a few minutes and with about 15 feet to go, I ran out of stones to step on. It’s either tracking back or getting wet. With a few other runners right behind me, it’s time to get wet.

It’s about a 3-mile uphill hike to Robinson Flat from there. It’s very hot and at times it’s very steep. A safety volunteer, who is sweating profusely, tells us that we are within a mile of the aid-station, but also makes it clear that it’s all uphill. I begin to hear the crowd with the noise undulating as the runners arrive there. A few yards before the aid station, I spot a most welcomed sight – a real bathroom. I quickly take care of business and make my way to the first medical aid station.

All runners are weighted ten times during the race, with the first time occurring at this station – Robinson Flat at mile 30. Weight is the best indication of hydration and ideally runners should be with 2% of their starting weight. Underweight means the runner is dehydrated and must drink more. Overweight is a more complicated problem, which can result from ingesting too little salt, too much salt, muscle inflammation, overexertion, or even kidney failure. Over-hydration is known as hyponatremia and even a 2 to 3% can lead to incoherence or even death from accumulation of fluid around the brain. Just last year, the first runner to reach the track at the finish line had failed to complete the race with 300 yards to go when he collapsed from hyponatremia.

The scale reads 161 pounds for me– that’s 6 pounds heavier than when I started. This is not good. I think I’ve been taking enough sodium, but maybe I’ve over done it. I can’t recall the last time I peed, which could mean problems with my kidneys. The medical personnel tells me to reduce my water intake and see how my weight is at the next medical aid station, known as Last Chance (at mile 43).

I don’t take anything from the Robinson Flat aid-station, as my crew member should be a few hundred yards after it. It’s 12:21 pm; I’ve been running for 7 hours and 21 minutes and I’m only 4 minutes ahead of the 30-hour pace. Joe Reis, my pacer and crew for this aid-station, flags me down and takes wonderful care of me. He had only gotten there about 45 minutes earlier and was hoping I had not already been there. He swaps my empty water bottles with new ones, which have ice-cold water. Gives me an Ensure to drink and proceeds to fill my pouches with GU and more salt tables. Dunks my hat and bandanna in cold water and fills both with ice. I ask him to place another TP kit (a precious commodity) in my back pocket while he tells me that my ultragirl friend passed here 25 minutes ago looking very strong. I knew his motives… despite the fact that she was a 10-time veteran of the Leadville 100-mile race, I was in theory a little faster runner than her. So, he was basically telling me, “She is kicking your butt, get going.” I didn’t take the bait. I was going to run this race at my pace, not someone else’s. Besides, I was happy for her.

I’ve already run a 50k race, but despite my weight gain, I feel strong. I am now in familiar territory so I push it a little harder and begin to gain time against the 30-hour clock and pass many runners. I pass Gordy, who tells me he’s lost his gas pedal. I take a quick detour for a potty break and realize that Joe didn’t give me that extra TP kit after all – he talks too much and gets distracted! I use my last one and hope not to need one again before mile 55, when I’ll get new ones from my crew. Between the Robinson Flat and the Last Chance medical stations at miles 30 and 44, respectively, there are two other “regular” aid stations at miles 34 and 38. At one of those aid stations, the one at mile 38 I believe, Rusty, a work-colleague spots me as I am departing. He had ridden his bike there somehow to come see me. His effort and friendship cheers me and encourages me to push it harder.

I’m running harder now; passing more runners and no one has passed me since Robinson Flat. As I catch runners, I spend a few seconds chatting with them and then move on. I have seriously curtailed my water intake, and even though I haven’t peed for hours now, I’m hoping that my weigh will be down when I reach the Last Chance medical station at mile 44. I get there at 2:21 pm; I’ve gained 1-½ hours on the 30-hour pace, and I am nowhere close to the cut-off. My weight hasn’t changed though, and given that it has now been a really long time since I last peed, it definitely points to my kidneys as the source. At high stress levels, the body produces an anti-diuretic hormone that shuts down the kidneys. I guess it’s the body’s way of conserving fluids at extreme conditions. I’m about to enter the most arduous part of the course, the two most difficult canyons and climbs; I must slow down to give my body a chance to recover and get rid of the excess fluid.

I powerwalk for a couple of miles and a few of the runners who I had passed begin to pass me. I want to push it, but I know that I need to give my body a chance to recover. Finally, at the bottom of the canyon, the flood gates open. Knowing that my kidneys have resumed working, I ingest a couple of GU’s with extra-caffeine and push it hard up Devil’s Thumb, the most difficult one mile climb in the entire race. I had avoided all caffeine for the month prior to this moment, knowing that I would need a caffeine rush precisely at this moment to make it up this mountain. It works. Going uphill, I pass all the runners who had passed me and then some, including four or five during the last 200 yards of the hill. A volunteer is waiting for me at the top, ready to refill my bottles and usher me through the aid station. I get weighted again; I’m still five pounds heavy, but since I have peed, I don’t worry about it.

One of the things that makes Western States so special are the volunteers. With 1,500 of them across the 25 aid stations, a volunteer is assigned to each runner as we enter each aid station. This volunteer literally takes care of the runner from the entrance to the exit. They are angels to the runners. They refill water bottles, get you food, encourage you and more. If I were not so sweaty and stinky, I would hug them and kiss them. Instead, I thank them profusely.

Devil’s Thumb is about at the mid-point mileage (mile 48) and a drop point for many exhausted runners. Chairs were filled with the carcasses of runners trying to recover. I barely spent a minute there and pushed on. The next 7 miles was the best section of my run. I felt great as I passed runner after runner. On the way down to El Dorado Canyon I spotted a runner ahead of me who had stopped in the middle of the trail. “What’s up?” I asked. “I just heard the roar of a mountain lion,” he said. “Stick right behind me,” I said as I passed him, “they don’t attack when there is more than one of us.” “And if they do,” I thought to myself, “they attack the slower one.” He kept up with me for a few hundred yards and then fell behind when he thought the danger was over. I came to another runner who was walking and was too tired to move to let me pass. I had to pass him by stepping off the trail.

I reached the bottom of El Dorado Canyon, refilled my water bottles at the aid station and proceeded to the feared 2-½ mile climb to Michigan Bluff. This was all familiar territory for me, and knowing that I would see my family in less than 50 minutes I pushed on. I knew which were the spots within 30, 15 and 5 minutes to the top of the climb, and this helped me stayed focused. Since Robinson Flat, I had probably passed 80 runners, and I was still passing runners on my way up to Michigan Bluff. I crossed the small stream at the 15-minute mark, I saw the 5-minute tree, and reached the top of the mountain strong. In a few hundred yards I would see everyone… I could already hear the crowd. With adrenaline flowing through my veins, I quickly reached the aid station and spotted my crew. The scale showed that I was still five pounds heavy, frustrating, but I ignore it. One of the volunteers prepared a “to go” paper container with watermelon and strawberries.

My nephew directed me to the where the rest of the crew was located. I had arrived to mile 55 at 6:51 pm. I had been running for almost 14 hours but felt strong. My crew swapped water bottles, removed all the trash from my pockets, put ice in my cap and bandanna, and gave me enough stuff (including TP) for just the next 7 miles since we would see each other at the Foresthill aid station again. There was still plenty of light, so I had no need for flashlights, but took a small one just in case I got hurt and had to slow down. I gave my wife a small pinecone that I had picked for her on the way up to Michigan Bluff – I wanted her to know that I had been thinking about her. I tried to use one of the portajohn’s there, but they were all busy – it would have to be al fresco on the way to Foresthill. My crew walked with me to the entrance of the trail, and off I went.

Joe, my pacer, was supposed to be waiting for me at the bottom of Bath Road (mile 60), but I got there quicker than he anticipated. (He must have been talking to someone.) A steep hill, I proceeded to powerwalk it, encountering Joe somewhere mid-hill. A quick run from the top of Bath Road to the Foresthill aid station put me there at 8:20 pm. I had moved up about 100 places and was now at number 176 and 3 hours ahead of the 30-hour pace. I had passed my ultragirl friend somewhere between Michigan Bluff and Foresthill, but I never saw her to say hello and run a bit together.

Still five pounds overweight, there was not much I could do about it. As if they were servicing a race car during a pit stop, my crew got me out of Foresthill in no time with a new shirt, flashlights, headlamps, windbreaker, and all the necessary accoutrements and nutrition supplies for my night run.

I had practically run alone for the first 60 miles. Sometimes, I would go miles without seeing a single soul. Having Joe with me was like having a security blanket. His job was to get me to the finish line, no matter what. Had I arrived by 7:00 pm to Foresthill, his instructions were to get me to the finish line within 24 hours. An 8:20 pm arrival made that nearly impossible. I still had 38 miles to go (1 and ½ marathons), much of it was going to be night running, and to do it in less than 9 hours would be difficult. Joe paced me by running about 20 feet ahead of me. We developed a nice rhythm, powerwalking the hills and running down hills and flats. Night enveloped us within an hour of our departure from Foresthill. At night, it was difficult for me to know if I was going uphill or not, and Joe would take advantage of this to cheat and make me run some of the uphills. We ran without much difficulty, past a couple of aid stations, until about mile 75 when my dark moments started.

I was beginning to feel that my urinary system was shutting down again, but this time, my GI system was following suit. I asked Joe to slow down a little to give my body a chance to recover, but my body was shutting down quickly no matter what. My intestines were trying to get rid of whatever was left inside them (even after 6 or 7 previous detours). This section of the course was somewhat open, with not many bushes to hide behind. “Joe, you’ve got to find me a ‘bathroom’,” I said, “and pronto.” “Hold on, let me find a nice rock,” he answered. Within a few yards, there was a small detour where Joe found a perfect spot. Two large, flat rocks side-to-side, about chair high, with about 6 inches of space between them. Joe shines the light on them as I stumble my way there. He continues to shine the light as I am about to take care of business so I say, “Hey, this is not a show… turn off the light and enjoy the stars while I provide the sound effects.” I guess a pacer and runner develop a sense of intimacy that only comes through the struggles of the runner. It’s similar to that of a nurse and patient.

“OK Joe, that takes care of the lower part of the intestine,” I said, “now I need to empty my stomach.” I drank water and forced myself to vomit. Not much would come out, but whatever little did cleared whatever I had left inside my GI. We continue walking and running to the aid station at mile 78 right before a river crossing. I was desperate for some Alka-Seltzer, but nobody had any, only Tums. By now, both my GI and my urinary tracks were shut down for business. I couldn’t drink, eat, or pee. Not a good time to be crossing a river, particularly not after 78 miles.

The volunteers had laid a rope from one side of the river to the other, so runners and pacers could hold on to the rope and not be dragged by its moderate current. The crossing is about 100 yards in length (or so it seems); the water is ice-cold and easily reaches our waists at the deep end. Joe is cracking jokes behind me while I am trying to keep my balance by finding solid footing between slippery stones, following a path of glow-sticks nicely placed by the volunteers at the bottom of the river to mark the best path. My fuel belt, wrapped around my neck to prevent my water bottles from floating downriver, adds to the balancing act; but, ultimately, I cross the river unscathed and relatively quickly.

I’ve been running for 20 hours now (with just one hour of sleep the night before), it’s 1:00 am, I am wet, shivering, and can’t drink, eat, or pee…. and I still have 22 miles to go. How in the world I’m going to get to the finish line, I don’t know. But I do know that my father and sister suffered infinitely more during their final hours, so I must simply dig deeper for fortitude. We walk the 2-mile steep hill to Green Gate. My nephew meets us a few hundred yards before the aid station, and, from his demeanor, I can tell my condition scares him. He runs back up to the aid station to get everything ready for me.

For the first time during 80 miles, I sit on a chair at the aid station so my crew can fix me best they can. I remove my shoes, ankle braces, socks and peel off the taping from my feet. Thanks to my taping job, plenty of lubrication, and double socks, my feet are in remarkably good shape. Just one blister on a big toe, which I proceed to lance and repair as my nephew squirms. I wash my feet with the one-gallon jug of water which my crew has carried two miles downhill. I dry them and apply a thick coat of Vaseline (to prevent blisters). The rest of my condition was such that some of the crewmembers for other runners took pity of me and assisted by shining lights on me while I fixed myself. I put on new outer shorts, leaving my compression shorts on, which is a good thing as otherwise the ice-cold water from the river crossing would have resulted in a pathetic show.

This was the longest pit stop; I was probably there for a good five minutes or so. I filled one of my water bottles with Gatorade and another with Sprite, hoping that I would be able to take small sips along the way. As I get ready to leave the aid station and announce my number (runners are tracked by their numbers in and out of every station), I realize that my bib is on the old pair of shorts. Joe takes care of it. I want to make a joke while he is pinning it, but I have no energy to speak, so I say nothing.

We continue walking for a little while, but I don’t think it’s fair to make my pacer walk. So, I run best I can. A couple of folks pass us, then we pass them and we trade places back and forth. These are very dark moments for me. I still can’t eat; I can’t even swallow a small GU. I barely have any energy. I knew I would reach a point during which the race would become all mental, and this was definitely it. I ask Joe to tell me how long it’s taking us from one ½ mile marker to the next. He tells me 7 ½ minutes. I can’t do simple math, so I ask him to help me figure out if we can still get there within 30 hours. So long as we keep this pace, we have plenty of time.

We reach the aid station at mile 85 after an almost two-hour struggle. I don’t remember much. I think I refill one of the water bottles with GU2O. The taste is disgusting; I empty it a few yards later. We are now entering relatively gentle territory; had I been in good shape, I would have been able to make great time here. I am surprised that people are not passing us… I guess they must be in equally bad shape. I think about last year, when I paced someone during the last 40 miles and how much he struggled. I’m putting my pacer through this struggle, but he continues to help me by pointing out and lighting the rocks and obstacles along the course for me. “Rock on the left, hole in the center, careful with this root.” We go through a few streams and he reaches out to help me across the rocks, “you can’t help me Joe," I say, "I would get disqualified.” So he simply shines a light.

The struggle continues for another ninety minutes before we hear the loud music coming from the middle of the woods. It’s the unmistakable aid station at Brown Bar. We are just about to get there drawn by the melody when I trip on a stone and land flat on my face – hard! I think I’ve broken my hand, or at the very least three fingers. I struggle to get up, while Joe is apologizing for not pointing that rock. “It’s not your fault Joe,” I said, “I’m responsible for my own footing.” This had been the first time I had tripped during the entire run; I guess the music must have distracted me for a fraction of a second. For almost 90 miles now, I had kept my eyes on the path 15 feet in front of me at all times. I had been concerned that a fall or ankle twist would end my race, as my ankle was still swollen and weak from its dislocation three months earlier. My ankle brace had helped all the way to mile 80, but I had removed it there, as I could no longer withstand its pressure.

We barely stop at Brown Bar. There are a few runners there in chairs. Three miles to the next aid station at the Highway 49 crossing, where I will have an opportunity to see my crew. I’ve yet to make a wrong turn, something always in the mind of every runner. Joe knows that I am concerned about this, particularly because he hasn’t run this portion of the course before. So every time he sees a yellow flag or a glow stick, both of which mark the course, he calls them out to me so that I know he is paying attention. He is doing at awesome job getting me to the finish line, but I am still struggling.

We no longer need our lights, the sun has risen for a second time, and my own darkness begins to dissipate. We finally reach the hill that will take us to the Highway 49 crossing at mile 93 of the course. “When you hear the cars, Joe, we are almost there,” I say. We walk the hill; we hear the sound of the cars; my nephew is waiting before the aid station. I have reached there totally exhausted, but I am in good spirits. I’m still heavy by 6 pounds; the medical personnel tell me not to worry, commenting that everyone is arriving heavy to this aid station. I get their green light to continue.

The aid station has potato soup. I decide to try it. It's tasty and hot and goes down quite easily. It feels great to finally be able to put something in my stomach. My urinary track had also resumed working a few miles back. My 20 darkest miles seem to be behind me.

I see my training buddy’s family. “Have you seen Eric?” they ask. “What are you talking about?” I respond, “I thought he would be celebrating at the finish line by now.” It’s 6:00 am, he should have been there by 5:00 am. Apparently he had problems with his knees after mile 60 or so. “I don’t think I passed him.” I said. “He was probably at one of the aid stations when you passed him and didn’t notice,” they say. “You know what this means,” his wife says, “he’ll want to do it again next year in 24 hours.” “I’ll pace him,” I say.

I don’t want to carry any extra weight, so I give everything but a bottle to my crew. “Do you want the cap?” they ask. “No, too heavy,” I respond. “How about your glasses?” No, too heavy. Just give me one water bottle and three salt tablets and take all my pouches from my belt. My nephew hands me a little bag with about ten salt tablets. “I only need three,” I say. “But they don’t weigh anything,” he says. “That’s too you, but not to me,” I say. The crowd is laughing at all my shedding.

I spend a little more time than usual at this aid station. I’m having a good time, which is lifting my spirits even more. I know the end is near, and I have plenty of time to get there. We take off with a cup of warm soup in hand (a refill) and my nephew in front of us taking pictures. I don’t think he was quite sure I would make it here from the last time he saw me, but he now knows that I’ll make it to the finish line, and he has learned a valuable lesson in the process. “I’ll see you there within three hours,” I say.

The last seven miles of the course have the toughest two hills of the last twenty miles. One of them is coming out of Highway 49 and the other is during the last two miles of the course. We walk the hill out of Highway 49, and we start running thereafter. It’s beautiful country here with open meadows. We are not running fast, but fast enough to pass runners. Joe is pushing me; he wants to get me to the finish line before 27 hours. He’s been so good to me during the entire night, that I let him push me.

We reach the no-hands bridge aid station. I thank the volunteers for being there, but I don’t stop. “Come on Joe, let’s get to the finish line.” Now he really begins to push me and with 3 miles to go, I begin to gripe. “Joe, I’ve done this part before, I need 50 minutes to get to the finish line, we can’t make it there in 40.” “Yes you can,” he says and pushes me as we continue to pass runners. I offer another runner the opportunity to trade pacers, “mine is a slave driver,” I say. Not surprisingly, he declines; his pacer is a much better-looking girl.

The last section of the trail is fairly difficult. Even Joe is commenting on the cruelty of putting such hills towards the end of the race, but he continues to push me nonetheless. We finally get to Robbie Point, which has a gate separating the trail from the road that takes the runners to the stadium at Placer High School, the finish line. There is a small aid-station here; we skip it as well. Now it’s up hill on the road. It’s 1.3 miles to the finish line and Joe wants me to run it in 10 minutes so I can get there in under 27 hours. It’s time to revolt. "No way," I say. "It’s my last mile; I want to enjoy it." The guy with the prettier pacer catches up to us, and she is encouraging him to push it. Joe’s competitive juices want me to race him. “Let him go,” I say, “He can’t get there in under 27 hours no matter how fast he runs, I know the course. We’ll get there soon enough and we’ll enjoy the last mile.” Joe can’t help but want to push me. “You run for it,” I say, “I’m sick”. My voice was literally gone by now. I could only whisper. The push during the last seven miles had left me feeling as if I had the flu.

The hill is now almost over and we have about ½ a mile to go. My nephew meets us there and is surprised that we made it so soon. “This guy has been pushing me all the way,” I complain to him. It’s a short downhill to the stadium. My nephew takes off so he can alert the rest of the crew and take pictures. I decide to pick up the pace a little to give the locals a good show. We reach the stadium -- here is where last year’s first arrival collapsed and was unable to finish the ¾, mostly-symbolic lap.

My ten-year-old son, Joseph, is waiting at the entrance and starts running on the track with me. I see my wife and she is clapping for me with tears in her eyes. My nephew is taking pictures. The crowd is cheering. My name is announced through the speakers as I cross the finish line in 27 hours and 4 minutes.

Epilog

A trail race is not a road race. Two marathons do not a 50-mile race make. Two 50-mile races don’t make a 100-mile race. And a “typical” 100-mile trail race is not a Western States Endurance Run.

For runners, climbing 18,000 feet and descending 23,000 feet across 100 miles of treacherous mountain trails during the heat of the day and chill of the night requires a totally different level of physical, mental, and logistical preparation. For the race director, orchestrating 1,500 volunteers across 25 aid stations in the Sierra Nevada to serve 400 runners during more than 30 hours is simply mind-boggling. But somehow, for 30 years now, it all comes together for the runners and the race director on the last weekend of every June.

Originally used by the Paiute and Washoe Indians, the Western States trail served for many years as the most direct route from the silver mines of Nevada to the gold camps of California. In 1955 a horse race was organized to prove that the 100-mile path from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California could be completed in 24 hours. This race, known as the Tevis Cup, became an annual event. In 1974, Gordy Ainsworth was the first man to join the horses on foot and completed the race even ahead of some of the horses. By 1977 the foot race had become an organized event and a year later was held separately from the horse race. Today, both races are held about three weeks apart, attracting contestants from across the world. Some 3,500 endurance athletes have finished the foot race and some have even finished both!

My race started about 18-months back when I qualified to Western States by running the, now in hindsight very easy, JFK 50-mile race in 8 ½ hours. Because there are more applicants than spots to the Western States race, an annual lottery is conducted to grant entries to the race. Being a non-profit organization that is always looking for funds to maintain and protect the trail, it also sells tickets to a raffle for two of the spots every year. With the purchase of enough raffle tickets, I knew I would have a better than a fifty-fifty chance at a winning entry, which is in fact exactly what happened.

With a race entry in hand and eighteen months to the race, all I needed to do was train. But how in the world do you train to run 100 miles across mountains, particularly for someone with very average running talent? For me, there was only one answer: learn from the best. So I hired seven-time Western States champion and course record holder, Scott Jurek, as my coach. Too bad he couldn’t also do the running for me.

Training for any race is a process of building a base, then sharpening and finally peaking on race day. Building a base requires months of long, slow distance running. Sharpening increases the intensity of the runs, including interval training and runs at lactate threshold. If done correctly, a runner should be able to peak on race day. These phases are completed through a process of stress and recovery during which the intensity of the workouts increase every week for three weeks followed by a one-week recovery at about half the intensity of the prior week. The four-week training cycle is repeated over and over (and over and over), at ever increasing intensities. Add to that a twice a week weight, strength-training program, an occasional 50-mile training race, hydration and nutrition testing while running, and you’ve got yourself the equivalent of a full-time job. Culminating a month before the race with about 20 hours of running per week, I often wondered which was more difficult and required higher discipline, the training or the race itself.

There is also a fine balance between injury and training. At such high mileage, the average body is prone to many injuries. I had my share of them, including a severely dislocated ankle (as in the bone out of the socket) just three months before the race. There is a saying at Western States that it is better to arrive to the race a little under-trained than a little injured, unfortunately most of us arrive there under-trained with injuries which the terrain has a phenomenal ability to uncover and exploit to increase its arduousness.

Eighteen months of training is a lifetime -- a lifetime during which I lost two of my closest friends to cancer, my father and my sister. The race took on a new meaning. It became my way to close these chapters of my life. It would also serve to rediscover my mental fortitude and to create a passage to a new phase of my professional career.

I spent the month prior to the race sleeping at 6,200 feet of altitude in Squaw Valley and training in the canyons during the heat of the day. It became apparent very quickly that the lack of mountains in Connecticut (where I live) was going to present a challenge during race day. I had tried to find the most difficult terrain in Connecticut, but the toughest mountains there are but gentle hills at Western States. During this last month, I met a good training buddy with whom I repeatedly trained on the last 70 miles of the course, including the last 20 at night. Coincidentally, we both had identical VO2 max levels and could run 1000-meter intervals at exactly the same speed, but his mountain training had made him a much stronger endurance runner. He would seemingly effortlessly run up the mountains, as I was left gasping for air far behind. He would run graciously down the steep slopes as if his steps had been choreographed to dance between the stones, while heavy-footedly, I would clumsily hold on for dear life.

My family and crew joined me at Squaw Valley a few days before the race. We spent a day visiting five of the twenty-five aid stations where they would crew for me. Because of the distance between the aid stations and times of the day during which I would pass by them, we spread aid-station responsibility among the crew. My pacer would take the aid station at mile 30 and then pace me from mile 60 to the finish line. Everyone would see me at miles 55, 62 and 100. And my nephew and his friend would handle night duty at miles 80 and 93.

Even though I had planned on retiring to bed early the night before the race, all the preparations with my crew prevented me from getting to bed before 11 pm. It was difficult to know exactly what I would need when, so my crew had to be ready for all eventualities. Change of shoes, change of socks, extra salt tablets, food which I might or might not want, blister repair kits, hot weather gear, cold weather gear, ice for my cap and bandana, toilet paper kits (baby wipes and paper towels), extra bottles, insect repellent, tylenol, tums, gas tablets, etc. Each member of my crew of five had a specific responsibility and each had to know what was expected of them. Everyone had to know what was in the crew bag, where it was, and when was I likely to ask for it. “Keep the large ice cooler in the car with all the food and carry small coolers to the aid stations. Give me the flashlights and headlight at mile 62, unless I arrive after 8:00 pm at mile 55, in which case I need them then.” Even with five pages of written instructions, the logistics can be unnerving for the crew, which must be attentively waiting at the aid stations for hours, ready to crew for a minute or two at most.

I laid out all my gear at a table before retiring to bed. Though I was staying right at Olympic Village, within a 5-minute walk of the 5:00 am start, I still made plans to wake up at 3:00 am, as I needed sufficient time to have some breakfast and tape certain portions of my feet to prevent blisters. In bed by 11:00, I was still tossing and turning by 1:00 am as my mind was being haunted by self-doubt. I had volunteered at a 100k race in Connecticut three months back. The director for that race, an accomplished ultra-marathoner who had even finished Badwater, the infamous 135-mile ultra across Death Valley, had failed to advance past mile 30 at Western States the prior year. The other volunteer at my aid station there had attempted Western States five times, and never gotten past Devil’s Thumb (mile 49), yet he had completed more than twenty-five, 100-mile races. The winner of that 100k race, an athlete from Monroe, Connecticut was also running Western States this year; I, on the other hand, had never run past 50 miles (80k). An ultragirl friend of mine running Western States this year for the first time was already a veteran of ten Leadville 100-mile races. My much stronger training buddy had run the 50-mile Leona Divide a full one hour faster than me. All these self-doubting thoughts had me tossing and turning until I finally managed to clear my mind by 2:00 am, barely catching an hour of sleep before all three alarms went off at 3:00 am.

I was at the starting line by 4:20 am. All I needed to do was to get my bib number. The mandatory medical check-ups and the weigh-in had been completed the day before. The large chronometer at the starting line counts backwards. With ten minutes to go, all 400 runners assemble outside. The sun has yet to rise and at 6200 feet of elevation, it’s cold. Five minutes to go. The crewmembers, fans, and news media jostle for position at either side past the starting line to cheer the runners. With ten seconds to go, everyone starts counting backwards… and at the gun, we all hit our chronometers and go.

The adrenaline is high and it takes the runners 2,000 feet uphill over three miles to the first aid station unnoticeably fast. Each aid station has a sign at its entrance with the times for the 24 and 30-hour paces and the absolute cut-off at the next aid station. The lead runners run well ahead of the 24-hour pace. Experienced runners and many veterans of this race (3,500 runners have crossed the finish line 6,000 times) try to keep just under the 24-hour pace. Less experienced runners and novices of this race, like myself, try to keep their pace somewhere in between. Those struggling for a multitude of reasons, simply try to make the cut-off’s from aid station to aid station. Arrivals past the cut-off time to any aid station are automatically disqualified and must stop. Many, of course, arrive to the aid stations well before the cut-off but drop anyway from exhaustion, injury, or even total incoherence.

I reached the first aid station within a minute of the 24-hour pace. I don’t know how I got to there so quickly. I wanted to be around a 27 hour pace, right in the middle of 24 and 30 hours. “Heck, maybe this is easier than I thought,” I naively said to myself and continued on after refilling my water bottles and eating the rest of my crushed muffin.

The final push to the summit of Squaw Valley – Emmigrant Pass – starts a few hundred yards after the first aid station. This climb, while short, reduced me to all four. The only way for me to “scale” it without sliding down was using my hands and feet. My gloves helped me grab on to rocks and make my way up fairly fast and quite safe. At 8,700 feet, we reach the highest point in the race. The view from the top is inspiring – I can see the entirety of the mountains framed by Lake Tahoe at the valley and pink clouds from the first rising sun above. The air is crisp and draws me to contemplate the scenery, but this is not the time.

Theoretically, it’s all downhill from here as the finish line is at 1,280 feet of elevation. It’s just the additional 16,000 feet of vertical climb and 23,000 feet of descent that would create the challenge.

The next section of the course is supposed to be mostly down, that is, mathematically speaking. But I guess 51% down and 49% up would qualify for this definition. While beautiful with wild flowers and phenomenal vistas, the terrain is relentless with rocks and small streams that make footing difficult. Second aid station is at mile 12. I reached there right at the 30-hour mark. What happened? I didn’t think I had slowed down that much and only a handful of people, including Gordy, the race’s founder, had passed me. I’m doing fine though. I’m peeing frequently, an important barometer, which tells me I am well hydrated. I’ve been eating well and nothing hurts too much. My feet, despite getting a little wet from many of the streams, don’t show signs of blisters. “Just run the race within your limits and don’t worry about the time at this early stage,” I tell myself repeating the advice from many Western States veterans. I push it just a little bit faster to the next aid station.

I reach the Red Star Ridge aid station at mile 16 under 4 hours, but barely 3 minutes before the 30-hour pace. I’m in 268th place out of 400 or so. This means that there are about 130 runners behind me, but I also know that in all likelihood about 150 will not finish… which puts me too close to the tail. How can this be? I am running strong. Yikes, this is beginning to look like a 30-hour finish, and I don’t like it.

Enter Duncan Canyon section. An area devastated by a forest fire four years ago, it’s a desolate place with burnt trees, no foliage, and an imposing arid terrain which exposes the runners to the direct heat of the sun. I continue to hydrate myself, take salt tablets, eat, and run at a sustainable pace. I’m still in unfamiliar territory, as I’ve never covered the first 30 miles of the course (My training buddy and I had tried running this section before the race, but we got lost as this part of the course is not marked until a few days prior to the race.) I’m expecting some down hills since theoretically there is a canyon here somewhere, but the down hills never come or I miss them between the hills. I arrive to the aid station at mile 24 after 5 hours and 39 minutes. The 30-hour pace is 5 hours and 40 minutes and the absolute cut-off at this station is barely 50 minutes later. I don’t like my situation. I haven’t peed for an hour but perhaps I’ve been sweating more due to the heat of this section. I refill my water bottles, fill my pockets with some boiled potatoes, put ice in my cap and push on.

Six miles to the next aid station and the first medical check point where I will also see a member of my crew. I had told him that I would be there between 11 am and 1 pm; unbeknownst to me, he is rushing to get there on time, as the traffic is heavy and the parking situation difficult. I reach a river crossing, which I presume is the bottom of the canyon even though it feels as if I had ran up to the river. Many runners are cooling off at the river. I carefully step on rocks while holding on to a fallen tree so I don’t get my feet wet. Wet feet are the ideal breading ground for blisters. After a few minutes and with about 15 feet to go, I ran out of stones to step on. It’s either tracking back or getting wet. With a few other runners right behind me, it’s time to get wet.

It’s about a 3-mile uphill hike to Robinson Flat from there. It’s very hot and at times it’s very steep. A safety volunteer, who is sweating profusely, tells us that we are within a mile of the aid-station, but also makes it clear that it’s all uphill. I begin to hear the crowd with the noise undulating as the runners arrive there. A few yards before the aid station, I spot a most welcomed sight – a real bathroom. I quickly take care of business and make my way to the first medical aid station.

All runners are weighted ten times during the race, with the first time occurring at this station – Robinson Flat at mile 30. Weight is the best indication of hydration and ideally runners should be with 2% of their starting weight. Underweight means the runner is dehydrated and must drink more. Overweight is a more complicated problem, which can result from ingesting too little salt, too much salt, muscle inflammation, overexertion, or even kidney failure. Over-hydration is known as hyponatremia and even a 2 to 3% can lead to incoherence or even death from accumulation of fluid around the brain. Just last year, the first runner to reach the track at the finish line had failed to complete the race with 300 yards to go when he collapsed from hyponatremia.

The scale reads 161 pounds for me– that’s 6 pounds heavier than when I started. This is not good. I think I’ve been taking enough sodium, but maybe I’ve over done it. I can’t recall the last time I peed, which could mean problems with my kidneys. The medical personnel tells me to reduce my water intake and see how my weight is at the next medical aid station, known as Last Chance (at mile 43).

I don’t take anything from the Robinson Flat aid-station, as my crew member should be a few hundred yards after it. It’s 12:21 pm; I’ve been running for 7 hours and 21 minutes and I’m only 4 minutes ahead of the 30-hour pace. Joe Reis, my pacer and crew for this aid-station, flags me down and takes wonderful care of me. He had only gotten there about 45 minutes earlier and was hoping I had not already been there. He swaps my empty water bottles with new ones, which have ice-cold water. Gives me an Ensure to drink and proceeds to fill my pouches with GU and more salt tables. Dunks my hat and bandanna in cold water and fills both with ice. I ask him to place another TP kit (a precious commodity) in my back pocket while he tells me that my ultragirl friend passed here 25 minutes ago looking very strong. I knew his motives… despite the fact that she was a 10-time veteran of the Leadville 100-mile race, I was in theory a little faster runner than her. So, he was basically telling me, “She is kicking your butt, get going.” I didn’t take the bait. I was going to run this race at my pace, not someone else’s. Besides, I was happy for her.

I’ve already run a 50k race, but despite my weight gain, I feel strong. I am now in familiar territory so I push it a little harder and begin to gain time against the 30-hour clock and pass many runners. I pass Gordy, who tells me he’s lost his gas pedal. I take a quick detour for a potty break and realize that Joe didn’t give me that extra TP kit after all – he talks too much and gets distracted! I use my last one and hope not to need one again before mile 55, when I’ll get new ones from my crew. Between the Robinson Flat and the Last Chance medical stations at miles 30 and 44, respectively, there are two other “regular” aid stations at miles 34 and 38. At one of those aid stations, the one at mile 38 I believe, Rusty, a work-colleague spots me as I am departing. He had ridden his bike there somehow to come see me. His effort and friendship cheers me and encourages me to push it harder.

I’m running harder now; passing more runners and no one has passed me since Robinson Flat. As I catch runners, I spend a few seconds chatting with them and then move on. I have seriously curtailed my water intake, and even though I haven’t peed for hours now, I’m hoping that my weigh will be down when I reach the Last Chance medical station at mile 44. I get there at 2:21 pm; I’ve gained 1-½ hours on the 30-hour pace, and I am nowhere close to the cut-off. My weight hasn’t changed though, and given that it has now been a really long time since I last peed, it definitely points to my kidneys as the source. At high stress levels, the body produces an anti-diuretic hormone that shuts down the kidneys. I guess it’s the body’s way of conserving fluids at extreme conditions. I’m about to enter the most arduous part of the course, the two most difficult canyons and climbs; I must slow down to give my body a chance to recover and get rid of the excess fluid.

I powerwalk for a couple of miles and a few of the runners who I had passed begin to pass me. I want to push it, but I know that I need to give my body a chance to recover. Finally, at the bottom of the canyon, the flood gates open. Knowing that my kidneys have resumed working, I ingest a couple of GU’s with extra-caffeine and push it hard up Devil’s Thumb, the most difficult one mile climb in the entire race. I had avoided all caffeine for the month prior to this moment, knowing that I would need a caffeine rush precisely at this moment to make it up this mountain. It works. Going uphill, I pass all the runners who had passed me and then some, including four or five during the last 200 yards of the hill. A volunteer is waiting for me at the top, ready to refill my bottles and usher me through the aid station. I get weighted again; I’m still five pounds heavy, but since I have peed, I don’t worry about it.

One of the things that makes Western States so special are the volunteers. With 1,500 of them across the 25 aid stations, a volunteer is assigned to each runner as we enter each aid station. This volunteer literally takes care of the runner from the entrance to the exit. They are angels to the runners. They refill water bottles, get you food, encourage you and more. If I were not so sweaty and stinky, I would hug them and kiss them. Instead, I thank them profusely.

Devil’s Thumb is about at the mid-point mileage (mile 48) and a drop point for many exhausted runners. Chairs were filled with the carcasses of runners trying to recover. I barely spent a minute there and pushed on. The next 7 miles was the best section of my run. I felt great as I passed runner after runner. On the way down to El Dorado Canyon I spotted a runner ahead of me who had stopped in the middle of the trail. “What’s up?” I asked. “I just heard the roar of a mountain lion,” he said. “Stick right behind me,” I said as I passed him, “they don’t attack when there is more than one of us.” “And if they do,” I thought to myself, “they attack the slower one.” He kept up with me for a few hundred yards and then fell behind when he thought the danger was over. I came to another runner who was walking and was too tired to move to let me pass. I had to pass him by stepping off the trail.

I reached the bottom of El Dorado Canyon, refilled my water bottles at the aid station and proceeded to the feared 2-½ mile climb to Michigan Bluff. This was all familiar territory for me, and knowing that I would see my family in less than 50 minutes I pushed on. I knew which were the spots within 30, 15 and 5 minutes to the top of the climb, and this helped me stayed focused. Since Robinson Flat, I had probably passed 80 runners, and I was still passing runners on my way up to Michigan Bluff. I crossed the small stream at the 15-minute mark, I saw the 5-minute tree, and reached the top of the mountain strong. In a few hundred yards I would see everyone… I could already hear the crowd. With adrenaline flowing through my veins, I quickly reached the aid station and spotted my crew. The scale showed that I was still five pounds heavy, frustrating, but I ignore it. One of the volunteers prepared a “to go” paper container with watermelon and strawberries.

My nephew directed me to the where the rest of the crew was located. I had arrived to mile 55 at 6:51 pm. I had been running for almost 14 hours but felt strong. My crew swapped water bottles, removed all the trash from my pockets, put ice in my cap and bandanna, and gave me enough stuff (including TP) for just the next 7 miles since we would see each other at the Foresthill aid station again. There was still plenty of light, so I had no need for flashlights, but took a small one just in case I got hurt and had to slow down. I gave my wife a small pinecone that I had picked for her on the way up to Michigan Bluff – I wanted her to know that I had been thinking about her. I tried to use one of the portajohn’s there, but they were all busy – it would have to be al fresco on the way to Foresthill. My crew walked with me to the entrance of the trail, and off I went.

Joe, my pacer, was supposed to be waiting for me at the bottom of Bath Road (mile 60), but I got there quicker than he anticipated. (He must have been talking to someone.) A steep hill, I proceeded to powerwalk it, encountering Joe somewhere mid-hill. A quick run from the top of Bath Road to the Foresthill aid station put me there at 8:20 pm. I had moved up about 100 places and was now at number 176 and 3 hours ahead of the 30-hour pace. I had passed my ultragirl friend somewhere between Michigan Bluff and Foresthill, but I never saw her to say hello and run a bit together.

Still five pounds overweight, there was not much I could do about it. As if they were servicing a race car during a pit stop, my crew got me out of Foresthill in no time with a new shirt, flashlights, headlamps, windbreaker, and all the necessary accoutrements and nutrition supplies for my night run.

I had practically run alone for the first 60 miles. Sometimes, I would go miles without seeing a single soul. Having Joe with me was like having a security blanket. His job was to get me to the finish line, no matter what. Had I arrived by 7:00 pm to Foresthill, his instructions were to get me to the finish line within 24 hours. An 8:20 pm arrival made that nearly impossible. I still had 38 miles to go (1 and ½ marathons), much of it was going to be night running, and to do it in less than 9 hours would be difficult. Joe paced me by running about 20 feet ahead of me. We developed a nice rhythm, powerwalking the hills and running down hills and flats. Night enveloped us within an hour of our departure from Foresthill. At night, it was difficult for me to know if I was going uphill or not, and Joe would take advantage of this to cheat and make me run some of the uphills. We ran without much difficulty, past a couple of aid stations, until about mile 75 when my dark moments started.

I was beginning to feel that my urinary system was shutting down again, but this time, my GI system was following suit. I asked Joe to slow down a little to give my body a chance to recover, but my body was shutting down quickly no matter what. My intestines were trying to get rid of whatever was left inside them (even after 6 or 7 previous detours). This section of the course was somewhat open, with not many bushes to hide behind. “Joe, you’ve got to find me a ‘bathroom’,” I said, “and pronto.” “Hold on, let me find a nice rock,” he answered. Within a few yards, there was a small detour where Joe found a perfect spot. Two large, flat rocks side-to-side, about chair high, with about 6 inches of space between them. Joe shines the light on them as I stumble my way there. He continues to shine the light as I am about to take care of business so I say, “Hey, this is not a show… turn off the light and enjoy the stars while I provide the sound effects.” I guess a pacer and runner develop a sense of intimacy that only comes through the struggles of the runner. It’s similar to that of a nurse and patient.

“OK Joe, that takes care of the lower part of the intestine,” I said, “now I need to empty my stomach.” I drank water and forced myself to vomit. Not much would come out, but whatever little did cleared whatever I had left inside my GI. We continue walking and running to the aid station at mile 78 right before a river crossing. I was desperate for some Alka-Seltzer, but nobody had any, only Tums. By now, both my GI and my urinary tracks were shut down for business. I couldn’t drink, eat, or pee. Not a good time to be crossing a river, particularly not after 78 miles.

The volunteers had laid a rope from one side of the river to the other, so runners and pacers could hold on to the rope and not be dragged by its moderate current. The crossing is about 100 yards in length (or so it seems); the water is ice-cold and easily reaches our waists at the deep end. Joe is cracking jokes behind me while I am trying to keep my balance by finding solid footing between slippery stones, following a path of glow-sticks nicely placed by the volunteers at the bottom of the river to mark the best path. My fuel belt, wrapped around my neck to prevent my water bottles from floating downriver, adds to the balancing act; but, ultimately, I cross the river unscathed and relatively quickly.

I’ve been running for 20 hours now (with just one hour of sleep the night before), it’s 1:00 am, I am wet, shivering, and can’t drink, eat, or pee…. and I still have 22 miles to go. How in the world I’m going to get to the finish line, I don’t know. But I do know that my father and sister suffered infinitely more during their final hours, so I must simply dig deeper for fortitude. We walk the 2-mile steep hill to Green Gate. My nephew meets us a few hundred yards before the aid station, and, from his demeanor, I can tell my condition scares him. He runs back up to the aid station to get everything ready for me.

For the first time during 80 miles, I sit on a chair at the aid station so my crew can fix me best they can. I remove my shoes, ankle braces, socks and peel off the taping from my feet. Thanks to my taping job, plenty of lubrication, and double socks, my feet are in remarkably good shape. Just one blister on a big toe, which I proceed to lance and repair as my nephew squirms. I wash my feet with the one-gallon jug of water which my crew has carried two miles downhill. I dry them and apply a thick coat of Vaseline (to prevent blisters). The rest of my condition was such that some of the crewmembers for other runners took pity of me and assisted by shining lights on me while I fixed myself. I put on new outer shorts, leaving my compression shorts on, which is a good thing as otherwise the ice-cold water from the river crossing would have resulted in a pathetic show.

This was the longest pit stop; I was probably there for a good five minutes or so. I filled one of my water bottles with Gatorade and another with Sprite, hoping that I would be able to take small sips along the way. As I get ready to leave the aid station and announce my number (runners are tracked by their numbers in and out of every station), I realize that my bib is on the old pair of shorts. Joe takes care of it. I want to make a joke while he is pinning it, but I have no energy to speak, so I say nothing.

We continue walking for a little while, but I don’t think it’s fair to make my pacer walk. So, I run best I can. A couple of folks pass us, then we pass them and we trade places back and forth. These are very dark moments for me. I still can’t eat; I can’t even swallow a small GU. I barely have any energy. I knew I would reach a point during which the race would become all mental, and this was definitely it. I ask Joe to tell me how long it’s taking us from one ½ mile marker to the next. He tells me 7 ½ minutes. I can’t do simple math, so I ask him to help me figure out if we can still get there within 30 hours. So long as we keep this pace, we have plenty of time.

We reach the aid station at mile 85 after an almost two-hour struggle. I don’t remember much. I think I refill one of the water bottles with GU2O. The taste is disgusting; I empty it a few yards later. We are now entering relatively gentle territory; had I been in good shape, I would have been able to make great time here. I am surprised that people are not passing us… I guess they must be in equally bad shape. I think about last year, when I paced someone during the last 40 miles and how much he struggled. I’m putting my pacer through this struggle, but he continues to help me by pointing out and lighting the rocks and obstacles along the course for me. “Rock on the left, hole in the center, careful with this root.” We go through a few streams and he reaches out to help me across the rocks, “you can’t help me Joe," I say, "I would get disqualified.” So he simply shines a light.

The struggle continues for another ninety minutes before we hear the loud music coming from the middle of the woods. It’s the unmistakable aid station at Brown Bar. We are just about to get there drawn by the melody when I trip on a stone and land flat on my face – hard! I think I’ve broken my hand, or at the very least three fingers. I struggle to get up, while Joe is apologizing for not pointing that rock. “It’s not your fault Joe,” I said, “I’m responsible for my own footing.” This had been the first time I had tripped during the entire run; I guess the music must have distracted me for a fraction of a second. For almost 90 miles now, I had kept my eyes on the path 15 feet in front of me at all times. I had been concerned that a fall or ankle twist would end my race, as my ankle was still swollen and weak from its dislocation three months earlier. My ankle brace had helped all the way to mile 80, but I had removed it there, as I could no longer withstand its pressure.

We barely stop at Brown Bar. There are a few runners there in chairs. Three miles to the next aid station at the Highway 49 crossing, where I will have an opportunity to see my crew. I’ve yet to make a wrong turn, something always in the mind of every runner. Joe knows that I am concerned about this, particularly because he hasn’t run this portion of the course before. So every time he sees a yellow flag or a glow stick, both of which mark the course, he calls them out to me so that I know he is paying attention. He is doing at awesome job getting me to the finish line, but I am still struggling.

We no longer need our lights, the sun has risen for a second time, and my own darkness begins to dissipate. We finally reach the hill that will take us to the Highway 49 crossing at mile 93 of the course. “When you hear the cars, Joe, we are almost there,” I say. We walk the hill; we hear the sound of the cars; my nephew is waiting before the aid station. I have reached there totally exhausted, but I am in good spirits. I’m still heavy by 6 pounds; the medical personnel tell me not to worry, commenting that everyone is arriving heavy to this aid station. I get their green light to continue.

The aid station has potato soup. I decide to try it. It's tasty and hot and goes down quite easily. It feels great to finally be able to put something in my stomach. My urinary track had also resumed working a few miles back. My 20 darkest miles seem to be behind me.

I see my training buddy’s family. “Have you seen Eric?” they ask. “What are you talking about?” I respond, “I thought he would be celebrating at the finish line by now.” It’s 6:00 am, he should have been there by 5:00 am. Apparently he had problems with his knees after mile 60 or so. “I don’t think I passed him.” I said. “He was probably at one of the aid stations when you passed him and didn’t notice,” they say. “You know what this means,” his wife says, “he’ll want to do it again next year in 24 hours.” “I’ll pace him,” I say.

I don’t want to carry any extra weight, so I give everything but a bottle to my crew. “Do you want the cap?” they ask. “No, too heavy,” I respond. “How about your glasses?” No, too heavy. Just give me one water bottle and three salt tablets and take all my pouches from my belt. My nephew hands me a little bag with about ten salt tablets. “I only need three,” I say. “But they don’t weigh anything,” he says. “That’s too you, but not to me,” I say. The crowd is laughing at all my shedding.

I spend a little more time than usual at this aid station. I’m having a good time, which is lifting my spirits even more. I know the end is near, and I have plenty of time to get there. We take off with a cup of warm soup in hand (a refill) and my nephew in front of us taking pictures. I don’t think he was quite sure I would make it here from the last time he saw me, but he now knows that I’ll make it to the finish line, and he has learned a valuable lesson in the process. “I’ll see you there within three hours,” I say.

The last seven miles of the course have the toughest two hills of the last twenty miles. One of them is coming out of Highway 49 and the other is during the last two miles of the course. We walk the hill out of Highway 49, and we start running thereafter. It’s beautiful country here with open meadows. We are not running fast, but fast enough to pass runners. Joe is pushing me; he wants to get me to the finish line before 27 hours. He’s been so good to me during the entire night, that I let him push me.

We reach the no-hands bridge aid station. I thank the volunteers for being there, but I don’t stop. “Come on Joe, let’s get to the finish line.” Now he really begins to push me and with 3 miles to go, I begin to gripe. “Joe, I’ve done this part before, I need 50 minutes to get to the finish line, we can’t make it there in 40.” “Yes you can,” he says and pushes me as we continue to pass runners. I offer another runner the opportunity to trade pacers, “mine is a slave driver,” I say. Not surprisingly, he declines; his pacer is a much better-looking girl.

The last section of the trail is fairly difficult. Even Joe is commenting on the cruelty of putting such hills towards the end of the race, but he continues to push me nonetheless. We finally get to Robbie Point, which has a gate separating the trail from the road that takes the runners to the stadium at Placer High School, the finish line. There is a small aid-station here; we skip it as well. Now it’s up hill on the road. It’s 1.3 miles to the finish line and Joe wants me to run it in 10 minutes so I can get there in under 27 hours. It’s time to revolt. "No way," I say. "It’s my last mile; I want to enjoy it." The guy with the prettier pacer catches up to us, and she is encouraging him to push it. Joe’s competitive juices want me to race him. “Let him go,” I say, “He can’t get there in under 27 hours no matter how fast he runs, I know the course. We’ll get there soon enough and we’ll enjoy the last mile.” Joe can’t help but want to push me. “You run for it,” I say, “I’m sick”. My voice was literally gone by now. I could only whisper. The push during the last seven miles had left me feeling as if I had the flu.

The hill is now almost over and we have about ½ a mile to go. My nephew meets us there and is surprised that we made it so soon. “This guy has been pushing me all the way,” I complain to him. It’s a short downhill to the stadium. My nephew takes off so he can alert the rest of the crew and take pictures. I decide to pick up the pace a little to give the locals a good show. We reach the stadium -- here is where last year’s first arrival collapsed and was unable to finish the ¾, mostly-symbolic lap.

My ten-year-old son, Joseph, is waiting at the entrance and starts running on the track with me. I see my wife and she is clapping for me with tears in her eyes. My nephew is taking pictures. The crowd is cheering. My name is announced through the speakers as I cross the finish line in 27 hours and 4 minutes.

Epilog

270 runners successfully finished the race within the 3o hour limit.

This year’s winner finished in an amazing 16 hours and 12 minutes. He was not even among the top 10 favorites.

Brian Morrison, my friend who last year arrived first to the stadium but did not finish, had to drop out at mile 38 this year. I'm sure he'll win it (again) some day.

Dan, the guy who I paced last year during the last 40 miles to a 27-hour finish, finished this year in less than 24 hours, earning him the coveted silver buckle.

Joy, my ultragirl friend and veteran of the 10 Leadville’s had to drop at mile 85, after 24 hours of running, from severe hydration issues. I’m sure she’ll be back.

J.L., the winner of the 100k-race in Connecticut finished in 28 hours and 18 minutes.

Eric, my training buddy pushed himself through the pain of a severe IT band problem on both knees and finished in 28 hours and 41 minutes.

Carl, the Connecticut race director and Badwater veteran ran Western States again this year and successfully completed it in 29 hours and 45 minutes.

Over 100 runners had to drop from the race for myriad reasons, including some who were totally delusional. 3 made all the cut-offs but arrived to the finish line just a few minutes after 30 hours and were disqualified.

My finish of 27 hours and 4 minutes placed me 153rd overall and was good enough for a bronze buckle. The guy who pushed it at the very end beat me but didn’t break 27 either.

I was ten pounds heavy by the next morning, probably the result of muscle inflammation. Within a couple of days, my weight was back to normal and all my body functions working properly. My fingers were still swollen from the fall, but not broken. My ankle never failed me.

I discovered that the training required more discipline than the race, but that the race was more difficult than the training. The prayers and support of friends and family, my coach Scott Jurek, my trainer Robin, 1,500 volunteers, work colleagues, my crew and my pacer got me to the finish line. I thank my wife and son for their patience and God for the opportunity, experience, and safe passage. I must now harness what I’ve learned and use it towards the benefit of mankind.

The final question everyone asks is, “Will you do it again?” The reason to do it again would be to finish it in under 24-hours!

.

.

THE END

.

.

.

.